Spike Wilner

Live at Smalls

Spike Wilner is intimitely linked to Smalls. The New York based jazz club, which he owns since 2007 and where he has been playing since 1994, is among the most respected in New York and in the world. If he is mostly known to the public as an entrepreneur, Spike Wilner remains an underestimated pianist, loving ragtime and bebop.

He was among the first students to benefit from the New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music at is creation in 1986 along with Brad Mehldau, Peter Bernstein or Larry Goldings where he was taught by jazz masters such as Jaki Byard or Walter Davis, Jr. Over the years, the New York musician developped a demanding conception of jazz and of the musician as an artist. Today, he works on forging an economic model specific to a jazz club and uses digital to expand its audience.

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Discography by Guy Reynard

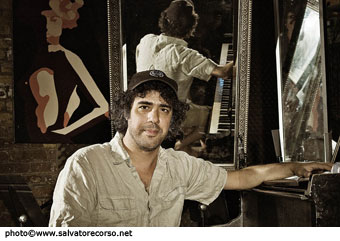

Photos Salvatore Corso et X © by courtesy of Salvatore Corso et Spike Wilner

© Jazz Hot n°667, Spring 2014

Jazz Hot: When did you start playing music?

Spike Wilner: My mom had a piano in the house and I started lessons when I was 6 or 7 years old. My first inspiration was ragtime music that I still love and play to this very day. I saw a TV show on Scott Joplin when I was very young and it made me want to play that music. I grew up in New York City but my dad got a job in Saint-Louis, Missouri, when I was 13. So he moved us there. One thing about Saint-Louis is the ragtime scene. So I became involved with that music over there. I ended up performing at a ragtime festival when I was 14. I saw Eubie Blake. He must have been 100 years old! That was a startling experience. My mom took me on my 16th birthday to see Oscar Peterson Trio and the Count Basie Orchestra. At the same time, I heard Maynard Ferguson. That was really exciting! Later, I worked with Maynard Ferguson. I had the opportunity to work with my childhood hero.

How early did you want to be a professional musician?

I never thought about being a professional musician. I just loved to play the piano and improvise. I never thought about it as a career. Even until now I don’t think about it as a career! (Laughs) In high school, we had a very challenging program with great musicians. Then I went to college originally for computers. But I was unhappy and wanted to play music again. One day, I read in the New York Times the New School for Social Research was going to start a new jazz program. I auditioned for it and was admitted. I was in the very first class. It was in 1986.

Could you describe what this program was about?

It was a very experimental, tiny little jazz program. There were thirty students. Arnie Lawrence who was a great musician ran it. He was a very spiritual minded jazz alto saxophone player. He got this program going. He put thirty students in one room with great jazz masters. It wasn’t a class; it was more of a forum. There was Tommy Flanagan, Art Blakey, Bill Dixon, Cedar Walton, Clifford Jordan, Jimmy Heath and many others. We would all gather in a big room filled with instruments and just play. Jimmy Cobb was our teacher for a while. He would play all day. That’s the greatest lesson you can have if you want to learn how to swing. He wouldn’t talk much. He would just play. We were so young. The implication of who they were in terms of the history of the music didn’t exist. I sometimes wish I could go back in time to relive the experience with those guys. My teachers were Jaki Byard, Walter Davis, Jr., Barry Harris and Kenny Barron. When I was young, Jaki Byard was this crazy old guy and I loved him. He was amazing. I still have the work he gave me. He was very connected to the stride piano and to traditional jazz music and he was a complete avant-garde musician. He had worked with Mingus, Eric Dolphy, … He had this duality and free mindedness. That’s what I do in my music. I like to have a strong connection to the tradition and recreate the tradition. I think of myself as a modernist, just like Jaki Byard is a modernist.

Who inspired you at that time?

I was very inspired by the traditional musicians that I loved the most: Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Tommy Flanagan. A pianist like Tommy Flanagan, for example, was my real hero because he was alive and I would go to hear him. He was very kind. Something about his music, the way he touched the piano, his connection to bebop, modern but traditional like a Teddy Wilson but with more bebop in him, all that made that I idealized him. The trio he had with Peter Washington and Lewis Nash was playing at the Village Vanguard. So I would go all the time. Now I have the very special privilege to play with Peter Washington and it’s like being with one of my heroes. I had great teachers but there also great piano players that were locals and that people may not remember their names who influence me, like Mark Thompson and Harry Whitaker. Brad Mehldau influenced me. He was my best friend at the time. We would practice together all day and hang out and go out at night. We were very close friends, same with Larry Goldings.

What qualities do you like in another musician?

I like to hear a good feeling and a tasteful music, musicians that can really phrase melodically and in the changes. I don’t want to hear fast or technical stuff. I think that people who can play in are more interesting. And if you know how to play in, you can play further out than anybody. But playing in is hard. Playing a melody is hard. Playing a good feeling is hard. Real jazz is a profound art that takes years of studying as well as years of emotional maturation in order to achieve the level of personal mastery that you have to become a great musician. My experience with the great masters is that they were always extraordinary people, fantastic human beings. It is a quality that is so deep about them that it is difficult to describe but it is something that you feel immediately.

What did you learn from the New School experience?

It taught me what it meant to be a jazz musician. I had the opportunity to be a part of a strong scene in New York City as it was very powerful. Senior members were still around. You could go to a club like Bradley’s and you would see Bobby Hutcherson, McCoy Tyner, Billy Higgins, Chick Corea, James Williams, Walter Bishop, Mulgrew Miller, Hank Jones, Ray Drummond, Kirk Lightsey hanging out. The young guys were Kenny Werner and Fred Hersch and I was just a kid compared to them. My very first teacher was Walter Davis, Jr. The lessons with him were about legend, not about music. I wasn’t advanced enough to appreciate what he would show me on the piano. He would tell me stories of hanging out with Bud Powell or Monk. One time he told me the story about how he was in a room with Charlie Parker, Monk and Bud. They were concentrating on bending a spoon on a table with the power of their minds. I didn’t realize until years later that he was just pulling my leg.

How many years did you study at the New School?

I was there for five years. Afterward it changed and became more academic. Artie Lawrence left and Martin Mueller made it more like a traditional school. I felt that this ruined the atmosphere. It was about sharing and being around artists. My classmates were Brad Mehldau, Peter Bernstein, Jesse Davis, Roy Hargrove and Sam Yahel. We were all hanging out and intensely studying this music. It was a very high level of music. I wasn’t even close to the level of those guys. It motivated me to work harder. By the time I graduated, I was a professional musician.

What were your early years like?

At that time, I had to do what every artist has to do in this time of his life, which is to explore and find himself. In my case, it took me a long time. I graduated in 1991. I was 24. I sold the Steinway that my parents gave me to live on being an artist. I got $8000 or $9000 dollars and made it last a year. New York was still cheap then. I was living in the East Village. Larry Goldings and Roy Hargrove started to tour immediately and spent their career on the road whereas I made most of my career playing in New York City. But I went on the road eventually with Artie Shaw, Maynard Ferguson. After the money of that piano ran out, I had to find a job. A restaurant opened on the Upper East Side and they needed a piano player and I got the job. It was 6 nights a week paid $100 a night or something. My first real time full gig was as the host of the Sunday afternoon jam session at the Village Gate.

In which clubs would you go to?

You had the Village Gate, the Blue Note, Bradley’s, Sweet Basil, Zinc Bar, Knickerbocker, the Angry Squire, so many. There were clubs all over New York at that time. And in the East Village, there were bars where everybody could play at. It was enough of a scene that you could make a living playing in clubs. For the first ten years of my career, I was playing clubs all over town. I wasn’t travelling that much.

What did you learn from your different experiences?

I developed a lot of skills that I think some artists are missing today. I did a lot of solo piano work at the Village Corner. I played Friday and Saturday nights from 9 pm to 3 am, so I learned a lot of songs. I had gigs with big bands. I toured with Artie Shaw’s big band lead at the time by Dick Johnson. It was the original charts from the Artie Shaw band. I really enjoyed it. I worked with Glenn Miller’s band and Maynard Ferguson’s.

Why did you go back to school later on?

I went to back to school in 2001 and got a master’s degree. I did one year at the Manhattan School of Music and my final year at the State University of New York. I felt that after ten years of playing, I should have an advanced degree to have the opportunity to teach at a university one day.

What is that you like in New York City jazz?

In terms of New York City, until recently, it was a bebop town. Bebop is New York City music. Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, Max Roach, Bud Powell, Jackie McLean made that sound here. They were New York City kids. Philadelphia guys like Coltrane would come to New York. When I was a kid, that feeling was very strong. Charlie Parker was the greatest musician that had ever lived. Charlie Parker is two things: the real blues feeling and romance playing the songs of the American songbook and abandonment to improvisation without forgetting that harmony is still a factor. Charlie Parker was the ultimate because he had the mastery of the melody, the rhythm and the harmony in a unified expression. Everything he played was so beautiful and so correct. Jazz musicians aspired for that correctness in their playing.

When did you understand what jazz was really about?

One time I saw a concert of Walter Davis, Jr., at Bradley’s. I must have been 19 years old. I was just started playing. I didn’t have much information. Walter was at the piano, I think Ray Drummond was on bass and I can’t remember who was on drums. There were also a few older African-American men that I met there. They were the real Harlem cultural crowd from when jazz was a real African-American art form, when that’s where you had to be when you wanted to listen to that music. White people were there but they had truly assimilated that African-American culture. I came from a background of being around African-American people all my life. My high school was 90 % all Black. The music in that culture always attracted me as something that I felt comfortable in. I was always amazed to see its subtleties. So at this concert, I was sitting at the bar. Next to me was this gentleman. Walter played something and started to laugh, and the bass player would laugh and the guy at the bar would laugh. I couldn’t understand what they were laughing about. And then it hit me. There was some kind of a communication happening, a language that was being spoken that was referential and joyful. That amazed me. It made me understand jazz at that moment. Since that time, I try to understand it more and more. Now the current jazz has become very serious. Besides being a virtuoso, John Coltrane’s real innovation was that he changed the mood of the music. He was the first jazz artist to come from a religious feeling. Bill Evans is serious too but before those guys there was Charlie Parker playing those funny jokes and rhymes but they were profound. Sonny Rollins has this joyfulness but robust. The seriousness took over. I think there was a concerted effort by the critics to destroy blues based jazz. But real jazz is like the truth: it doesn’t die. It hides out in little corners and comes back again. You see it re-emerging. My generation got the message. Peter Bernstein is a perfect example. Roy Hargrove is an incredible example of this music.

When did you first hear about Smalls?

In 1994, Grant Stewart told me about the opening of a new club and that he was going to be playing there. Mitch Borden ran this little place and it became popular because you could bring your own beer and young people would come to hang out. It was opened all night long so it attracted an eclectic crowd, young people, musician, homeless people, drug addicts, … It was wild. It wasn’t the best environment to play music in. That’s one thing people don’t like to hear about the old Small’s because it is so beloved. Back then, I was booked on Fridays and Saturdays and it was so loud that I couldn’t hear myself play. It was like playing in a cave of people screaming. That’s the difference between the old Smalls and now. Now people are really here to listen. But those days were fun. I started playing at Smalls during its very first year. Mitch supported me and believed in me. He gave me a chance and a study job from 1994 to 2002. Smalls is a forum for all kinds of musicians and an energy vortex. Certain artists made home for themselves and used the club to grow and develop their own style. Jason Lindner, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Mark Turner, Sam Yahel, Omer Avital were regulars.

How much has September 11 affected New York?

September 11 changed the city. Rents became very expensive. For example, Times Square used to be filled with little bars, porno shops, drugs, etc. It was a weird place. Then it was shut down and remained closed for years and was cleared out. Now there’s Disney, Chase Bank, etc. This happened all over the city. The rents were raised so high that people had to leave.

And what about the jazz scene?

After September 11, a lot of clubs, including Smalls, had to close because they couldn’t afford to pay the rent. Smalls’ went from being $800/month to $8000/month. It was impossible for Mitch to do what he did. Now you have to spend so much money to make a business run that there is a very fine margin on how to make living. The clubs that survived were the institutions like the Vanguard. The Blue Note was the first club to think corporately and was smart about doing their business.

How did the musicians and Smalls hold up?

Everyone was going broke. The work was gone. It became uneconomical to do anything. Smalls went bankrupted. Mitch went on to work at the Fat Cat. At that time, I left for Europe. It was too hard to be in New York after September 11 and Smalls’ closing. I was in and out of the country for about five years. When I got back, Smalls became a new bar with a Brazilian name. It wasn’t doing well. Many people that came were asking about Smalls and then left. The new owner called Mitch and suggested that they should both re-open Smalls. This lasted from 2004 to 2006 because it wasn’t making money. So I came in with another guy and bought the business in 2007. I organized things a little differently to make enough money to survive. We have a bar with a liquor license and raised the cover charge. We live economically. The musicians aren’t paid much. The music that is being played here has historical importance. That’s why we record all the concerts, night after night. This database is online. Now we have more than 6000 thousand recordings. The other idea I had was to stream the shows in the same way like in the old days you could hear Count Basie on radio play in a club. It became popular. There is also Smalls Live that was launched in 2008 to make projects that we own.

What have you achieved at Smalls?

One thing that I am proud of over the years is that I’ve created a recognizable brand of super quality jazz music.

Is there a specific sound to Smalls?

The funny thing about Smalls is that everyone wants to play tunes. Ethan Iverson will do his Bad Plus music all over the world but when he comes to Smalls, he just plays standards. There is something about the club that makes people want to be a little more traditional. Smalls is traditional club. We’re a bebop club at heart.

How do you choose the musicians that play at the club?

To me, the only thing that allows me to make the decisions at Smalls is my music. I have to be as good or better as the artist that plays here. The guys that play at Smalls have to be better than me, or at least as good as me. Not a lot of guys can do that. I don’t mean that as a joke. I have credibility because I cannot be contested by anyone who plays here.

Has running a club changed your playing?

It has given me the confidence to be a master. Before Smalls, I would get nervous about playing a gig. Today I have so much work to do before I get to play the piano that I am very happy when I can finally play. It’s made me love the music so much that I realized it is the salvation. I don’t have an aspiration for a career but I have an aspiration to be an artist. It made me better and better. It makes me love music more. At the club, I like to see guys that work hard and that are humble artists. To me, that is a sign of greatness, when you can just speak with your instrument.

*

http://www.smallsjazzclub.com

Smalls : 183 W 10th St, New York, NY

Discography

Spike Wilner/Le musicien

Leader Leader

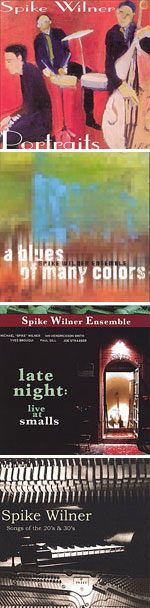

CD 1998. Portraits, Orchard X1079

CD 2000. Blues of Many Colors, Fresh Sound New Talent 130

CD 2004. Late Night : Live At Smalls, Fresh Sound New Talent 18

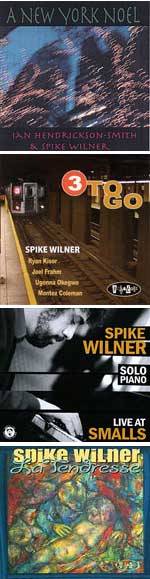

CD 2006. A New York Noël, Spike Wilner

CD 2006. Songs of the 20's & 30's, Spike Wilner

CD 2008. 3 to Go, Rhombus Records 8035

CD 2010. Solo Piano : Live at Smalls, Smallslive 0016

CD La Tendresse, Posi-Tone Records 8094 (date)

Sideman

CD 2000. Anthony Warlow, On the Boards, Polygram 5134022

CD 2001. Yves Brouqui,Live at Smalls, Elabeth 621040

CD 2005. Planet Jazz, In Orbit, Sharp Nine Records 1036

CD 2010. Cyrille-Aimée Daudel, Live at Smalls, Smallslive 0018

CD 2012. Tyler Mitchell, Live At Smalls, Smallslive 0030

CD 2012. David Schnitter, Live at Smalls, Smallslive 0031

Spike Wilner Producteur / Label Smalls Live

CD 2008. The Ryan Kisor Quintet, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0001

CD 2009. Ethan Iverson Trio, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0010

CD 2010. Jazz Incorporated, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0017

CD 2011. Bernstein , Goldings, Stewart, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0022

CD 2011. Jesse Davis Quintet, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0026

CD 2012. Harold Mabern Trio, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0032

CD 2012. Frank Lacy, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0038

CD 2013. Rodney Green Quartet, Live at Smalls, Smalls Live 0036

Videos

2006 Spike Wilner Trio Live At Smalls : Paul Gill (b), Mark Taylor (dm)

2011 Blues in B Flat Joel Press Spike Wilner at Smalls Jazz Club

2011 I Remember You Joel Press Spike Wilner at Smalls Jazz Club

2012 Spike Wilner at The New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music Interview

2013 Smalls Family Afterhours & Jam Session Hosted by Spike Wilner (Spike Wilner p, Behn Gillece vib, Melissa Aldana ts, Dezron Douglas b, Joey Saylor dm)

2013 Smalls Club Owner Spike Wilner Talks History, Streaming, Music Interview

2013 Spike Wilner Trio : Spike Wilner (p), Yotam Silberstein (g), Paul Gill (b) Padova Jazz Festival

2013 Spike Wilner Trio : Spike Wilner (p), Yotam Silberstein (g), Paul Gill (b) Smalls Jazz Club

*

|

|