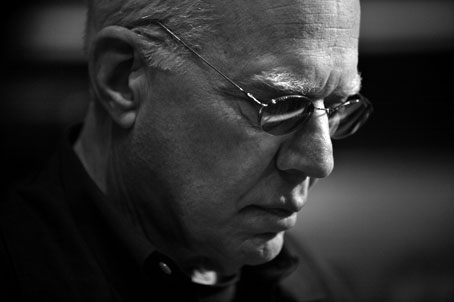

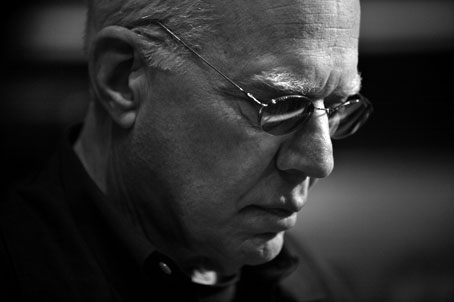

Steve Kuhn

A Quiet Man

At the top of his art, Steve Kuhn celebrated his 76th birthday on March 24th, 2014. His phrasing, technique, serenity and sense of melody make him an exceptional musician. In 1960 at the Jazz Gallery, in New York, John Coltrane was in the process of putting together the most famous quartet in the history of jazz. After Cedar Walton and Tommy Flanagan, he brought in a young pianist that had just left Kenny Dorham's band (1959-1960): Steve Kuhn was only 21 at the time… He played with the sax player for eight weeks, six nights a week. It was a key experience for the young artist even if McCoy Tyner was to replace him.

Steve Kuhn received a classical training in Boston with Margaret Chaloff and started his career with her son Serge Chaloff when he was 13. He graduated from Harvard while playing clubs every night with Arnold Wise and Chuck Israels. He also played with Stan Getz (1961-1963) and Art Farmer (1964-1966) before leading his own trios, an ensemble he is particularly fond of. In the past years, he has been playing with Steve Swallow and Billy Drummond. As a composer, he has built a wide repertoire and some of his originals have become standards. His musical personality and long-term collaboration with ECM demonstrate his ongoing search for new musical colors in which groove and soul elements are subtly present. After his debuts in a gospel-tinged jazz, the son of Hungarian immigrants found his voice in a music that is as lyrical but more tempered, which he is a master at. Music is about "reaching people emotionally. And that's [his] raison d’être." A fine motto!

Interview by Mathieu Perez

Discography by Guy Reynard Portrait © photo X by Courtesy of stevekuhnmusic.com

Other photos © Serge Baudot

© Jazz Hot n° 667, Spring 2014

Jazz Hot: You studied with Margaret Chaloff. What did you learn from her?

Steve Kuhn : I met her when I was twelve years old. I had started studying when I was five in Brooklyn where I was born. And then we moved to Chicago and I had a teacher there. We moved to Boston when I was twelve. And we had heard of her as a teacher. She was completely decidated to teaching. She taught what is called the Russian school of piano technique which enables you to play as fast or slow as needed always with the sound in mind. The projection of the sound is a natural piano sound. You push from the feet, and the sound comes up the leg through the knee up to the hands and mouth and you are blowing into the keys as if you are playing a horn. It’s the same breathing from the diaphram. It doesn’t matter if you are a bass player, a drum player, a horn player or a pianist. A lot of pianists play with tensions in the forearms and the sound is blocked there. I played Chopin, Bach, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov. Just classical music. But her son Serge Chaloff was a great jazz musician and she had a great love of jazz. And she knew Charlie Parker’s music very well.

Have you always been immersed in jazz?

When I was a baby, my father had a collection of 78 rpm records. He would play those records and I’d respond very well and I’d get very excited. I could recognize the labels of a record. Because I responded this way to the music, I always knew I wanted to be a musician. When I was five years old, my father insisted that I take piano lessons but I was board because I would have to play the same things the same way over and over again. So to keep up my interest, my teachers would give me a boogie woogie piece to play. That would be my reward. I wanted to improvise.

You studied in Harvard?

I was fortunate enough to get to Harvard. I majored in music but I didn’t go there for the music. Every undergraduate has to major in something so I chose music theory.

How was jazz perceived back then?

I was the black sheep. For the most part, the faculty didn’t recognize the music after Stravinsky. And jazz was worse than no music. There was no respect except from Walter Piston 2, who was a well-known classical composer back then. It was his last year as a teacher before retirement, so he was very relaxed. He was teaching techniques of 20th century composition. So every week he would assign to the class something in the twelve-tone or else. He had respect for jazz. Except for him, most of the teachers were grounded in Palestrina 3, Bach and Beethoven.

Were any of the students interested in jazz?

I was with classical musicians. I can’t think of anyone who graduated from Harvard and went into jazz before I did.

After Harvard, you attended the Lenox School of Jazz program.

I got a scholarship for three weeks. It was in the summer of 1959. Bill Evans, Gunther Schuller, George Russell and Kenny Dorham were teaching. The students were divided in groups. That year Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Gary McFarland were students too. I was put in a group with Ornette and Don.

Was it your first experience with other jazz musicians?

I started working when I was thirteen years old. I worked around Boston subbing for musicians. I was very fortunate when I was young. I played solo piano at the Stable and Storyville that was owned by George Wein. I was like a child prodigy and it was all in the papers. Then I played with my trio behind horn players like Coleman Hawkins and Chet Baker.

Many musicians who followed this program made great careers and became important jazz musicians. At the time, you met Gary McFarland 4 with whom you recorded The October Suite: Three Compositions of Gary McFarland en 1966.

Gary had no formal training. He was a natural. He went to Berklee School briefly in Boston and he didn’t like it at all. And he went to New York after that. Ornette came to New York when I did in the fall of 1959. And he started working with Don Cherry and the group of Charlie Haden. When I got to New York I called different people that I met at Lenox and in Boston. I called everybody I knew. Kenny Dorham was looking for a piano player for his quintet. And I worked with him in a part of Brooklyn called Bedford Stuyvesant which was all-Black. I was the only white guy in the band anyway. We toured in different places, in Canada, in the USA.

Back in 1959 at Lenox. Gunther Schuller played a great role in your life. What relation did you have with him?

I admired Gunther greatly because he had an incredible knowledge of music and classical music and he loved jazz. He used to have a radio program in New York on 20th century music. And every week, he would go chronologically from 1900 to the mid-1950s. Whenever I could I listened to that program. It was a great education just to hear this music. He was completely dedicated to the music. That’s what I admired. And it was the same for Coltrane. It was the two that I saw in my early years in New York who were focused on the music and they lived and breathed the music.

Bill Evans is probably the pianist with whom you have the strongest affinity. When did you meet him?

I met him for the first time when he was playing with George Russell’s band at Brandeis University. He was ten years older than I and much more together musically than I was. He was doing what I was trying to do. So I had to get my own voice. I had to learn from this. Initially when I came to New York, a lot of people compared me to Bill.

What did you appreciate most about the musician?

Bill was an incredible side reader. He could look at a piece of music and play it. Which is something you develop by doing it a lot. He had a wonderful technique but never used it for the sake of technique. He underplayed. Probably my sense of swing was a little more intense than his. I was probably more influenced by swing music and Charlie Parker and people like that.

Have you always been interested in twelve-tone and serial music as much as in jazz?

Gunther exposed me to a lot of that stuff through his radio program. I was very interested in Messiaen 5, John Cage 6, Boulez 7. Whatever influence it had on me. For a while I was playing more free, more Cecil Taylor like if you will but yet incorporating what I do. I was looking for my voice.

Is it after Lenox that you played with Kenny Dorham?

I played with Kenny two or three weeks. Kenny was a sweetheart, a wonderful talented guy. He composed, he played the piano, he was a good singer which a lot of people don’t realize. And he had a wonderful sound on the trumpet. Very warm. Unfortunately he admitted he was bitter that he didn’t have the recognition that Dizzy or Miles had. He felt he was right up there with them. He was a special player but not focused 100 % on the music. He was chasing the ladies and liked to get high a little.

You were playing in Kenny Dorham’s trio when you heard that John Coltrane had left Miles Davis. How did you meet Coltrane?

He’d left Miles. I got his phone number and I called him. ‘I know you don’t know who I am but I’m currently working with Kenny Dorham and I would love if we could just meet and talk about music and play a little.’ A week or two later he called me at the hotel where I was living. I guess he had called Kenny or asked around or something. We met in a little studio right around the corner of my hotel in Midtown in a room that was the size of a postage stamp. There’s was an upright piano and a chair that he sat in. And we played a little the music I was familiar with. And we talked. He didn’t say anything in particular afterwards. He thanked me. Another week or two passed and he called and said if I would like to come out to where he lived in Queens. His wife would cook dinner and we could sit and talk and play. So I took the subway and we did the same thing as we did in the rehearsal studio. He drove me back into Manhattan. He didn’t say anything more than that. Some time after, the phone rang in the hotel and he said ‘Would $135 a week be okay to start ?’ I was making $100 a week with Kenny. So it was not only a raise but the idea to play with him. I was very very happy.

You were playing at the Jazz Gallery.

He was hired for two, four weeks to work at the Jazz Gallery in New York and he kept getting held over for another two weeks. He wound up working there for 26 weeks in a row which is unheard of. Nobody works at a club for more than a week. I was with him eight, ten weeks, six nights a week. It was a wonderful experience. I’ll never forget it. I knew after that he wanted McCoy Tyner originally who was working at the time with the Jazztet with Art Farmer, Benny Golson and Curtis Fuller. He had a contract with them so he couldn’t leave. But John never told me this when he hired me. After eight, ten weeks McCoy was free and joined the band. That period I spend with him was very special. He soloed and the musicians soloed. We had plenty of time to do our thing. He didn’t speak much. He was very humble, very quiet. His dedication to the music was very special. It was inspiring to be around him. After that I went back to Kenny Dorham for another six months. I got a call from Scott LaFaro saying that Stan Getz came back from living in Copenhagen and wanted to put a quartet together. Scott said that if he got the rhythm section that he wanted then he would join him. At the time he was working with Bill Evans. We met with him and Pete La Roca at the Village Vanguard and played together. And he hired us. That was the original quartet in 1961. After two weeks, Scott was not happy with Pete La Roca. He wanted to hear more of the drums and less the cymbals. Pete like the cymbals a lot. Scott told Stan he was going to leave unless he got another drummer. He wanted Roy Haynes. So that’s what happened and that was the quartet until Scott was killed. It was a horrible tragedy. Just four or five months after the band started. To this day I miss him. He was an extraordinary talented guy, and a health addict.

You played in Stan Getz’ trio. How was it to work with him?

I played two years with Stan with an eight month hiatus in between. After Scott died, John Neves, a friend of mine from Boston, came in. And we played with Roy Haynes until the band broke up. And eight months later Stan called me and asked me to join him again with Hal Hairwood and Tommy Williams. We stayed together for about a year. And that ended and I joined Art Farmer with Pete La Roca and Steve Swallow after Jim Hall left. Stan was a great player but had many personalities. He could be a wonderful and horrible at times. It depended on how much he had to drink or how much cocaïne he had. He was very insecure. I remember after I left Coltrane, both Coltrane and Stan were hired on the same bill. Stan was so paranoid about Coltrane. John was the hottest thing going at that time. Stan felt very insecure and he had no reason to feel that way because he was a great player. They just played differently. But Stan was crazy that week that we played together. He kept saying : ‘I know you’d rather play with him than me.’ It was a difficult week for him. He was not a happy camper.

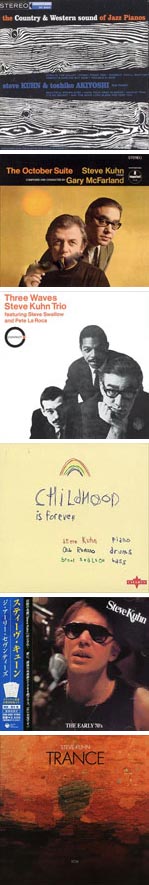

What was the context of your first album Country and Western Sound of Jazz Pianos in 1966?

Originally the producer Tom Wilson had a record company in Boston, he was a Harvard graduate as well, a little older than I, and he started a company called Transition Records. He was the first one to record Cecil Taylor. He came to New York and worked for United Artists for a while. I guess he knew me from Boston or Harvard. I met him in 1958 when I was playing with the trio I had, Chuck Israels and Arnold Wise, who both ended up playing with Bill Evans years after that. For United Artists, we went to New York and did this trio recording which never came out. I still have the tape and the test pressing. Maybe I’ll release it someday. It was the first time I ever recorded. For Dauntless Records, the jazz label of Audio Fidelity, Tom Wilson thought it would be commercially interesting to mix the jazz piano sound with country music. He wanted two pianists, Herbie Hancock and me, but Herbie was not able to do it at the time. And it became the Japanese Toshiko Akiyoshi. Eddie Summerlin arranged the songs for two pianos. There was Garry Galtbraith at the guitar, two bass players, John Neves and David Izenzon, and Pete La Roca. He was hoping to get both the country audience and the jazz audience and it turned out he got neither.

Steve Swallow remained a close friend over the years. Did you meet him while working on Three Waves in 1966?

I met Steve before the Three Waves album in the early 1960s. We had worked together in different situations. He’s the brother I never had. Jim Hall was working with Art Farmer and when he left, Steve suggested that I join them. So he hired me. We worked together for about a year.

Why do you prefer the trio ensemble?

That’s the unit I enjoy the most. A fourth musican makes something different. The trio concept is a conversation. It’s about a democracy. We all listen to each other. It can go in any direction. And I learned that early on listening to Ahmad Jamal’s and Bill Evans’ trios. It was good lesson. I try to keep that going. When you’re young, you tend to want to play everything, you want to tell your lifestory, and fast. As I’ve gotten older I sort of slowed down and thought more the music coming from the heart. For me that’s how you reach people. It’s not how fast you play or how you reharmonize. It’s about reaching people emotionally. And that’s my raison d’être.

There are few originals in your first albums. Is writing difficult?

Writing is difficult. In 1969, in Paris, I recorded Childhood Is Forever with Steve Swallow and Aldo Romano. At the end of that recording I had recorded every song that was in my repertoire. I needed new material. And Steve, to his credit, got on my case and said I needed to write more. At the time I was living in Sweden with my wife, who was a singer and would play with us, and she got on my case as well. In the summertime of 1969, I wrote thirteen songs in about two months. And I wrote lyrics to some of them as well.

You lived in Stockholm from 1967 to 1971, was it a call for jazz?

I fell in love with a Swedish actress. She also was a singer. A wonderful comedic and serious actress. She made a number of films. Her name was Monica Zetterlund. We lived together for four years. Living in a foreign country was a wonderful experience. I worked a lot in Scandinavia at the time. I had a trio with Palle Danielsson et Jon Christensen and different bass players and drummers like Aldo Romano. We worked with Monica sometimes. In those days, the European public seemed to be more into jazz. There’s this tradition in Europe. They have more respect for the artists. That doesn’t exist in the USA. It’s better now.

When did start collaborated with ECM which is still your current label? Was it your album The October Suite that caught the attention of Manfred Eicher?

I was living in Stockholm when Manfred Eicher created his company. I had heard that he was interested in me. When I came back to live in New York, he contacted me saying he would like to do a project. And we went back to phone and mail. Our first recording was in 1974.

From 1974 to 1984, most of your albums featured originals.

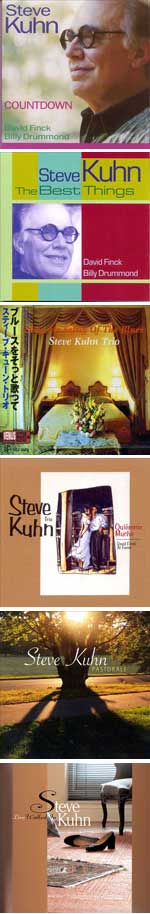

ECM asked for originals. It forced me to write. Manfred Eicher’s a wonderful producer. He’s extraordinarily talented at what he does. He started this company and it has done very well. It’s one of the companies left that still makes recordings.

Were the albums Ecstasy and Trance made at the same time?

Ecstasy was done in New York then I went to Oslo to mix it. When we were in Norway, he said if the studio was available he want me to do a solo recording. That’s how Trance came about. I had no idea of what I was going to do. The studio was available and we did it in three hours. I was amazed. Manfred is a great guide.e.

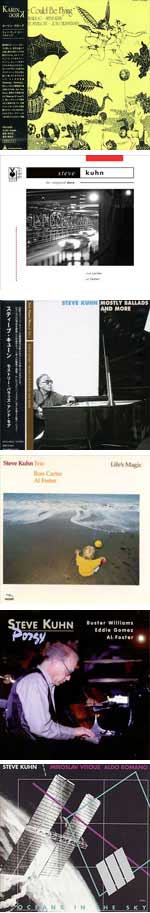

How did the albums, Pavane for a Dead Princess (2006) and Baubles, Bangles and Bead (2008), in which you reinterpret the work of classical composers come about?

It was for Venus Records. We recorded Pavane for a Dead Princess and Baubles, Bangles and Beads. I did a lot of records for them. The producers wanted records with classical music. I chose the titles I grew up with and others that I liked most. I went through the fakebook, arranged the tunes and changed the harmonies so that I could play them. The albums sold well in Japan. It was a challenge.

You recorded Mostly Coltrane and play at the annual tribute concert at Birdland. What period of Coltrane is highlighted?

We did a lot of stuff from the late Coltrane that I wasn’t familiar with. At the time Joe Lovano was doing the annual concert and he brought a lot of Coltrane’s later works. I didn’t fallow Coltrane at that time and I didn’t know the tunes well. I had to learn them and play them in a way that I could personalize them. It was fun.

*

1. Julius et Margaret Chaloff

2. Walter Piston

3. Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

4. Gary McFarland, cf. www.dougpayne.com

5. Olivier Messiaen

6. John Cage

7. Pierre Boulez

Contact : http://stevekuhnmusic.com/

Discography

Leader Leader

CD 1963. Country and Western Sound of Jazz Pianos, Dauntless Records 6003

(LP Dauntless Records 6308)

CD 1966. The October Suite: Three Compositions of Gary McFarland, Impulse! 23035 (LP Impulse! 9136)

CD 1966. Three Waves, BMG 38085

CD 1968. Watch What Happens, MPS 9019

LP 1968. Steve Kuhn in Europe, Prestige 7694

CD 1969. Childhood Is Forever, Charly Records 129 (LP BYG Records 529136)

CD 1971. Steve Kuhn, Sony COCB-53597 (LP Buddah Records 5098)

LP 1972. Raindrops (Steve Kuhn Live in New York), Muse MR-5106

CD 1974. Ecstasy, ECM UCCE-3004 (LP ECM 1058)

CD 1974. We Could Be Flying, P-Vine Records 22061 (coleader Karin Krog)

CD 1974. Trance, ECM UCCU 5248 (LP ECM 1052)

LP 1977. Motility, ECM 1094

LP 1978. Non-Fiction, ECM 1124

LP 1979. Playground, ECM 1159 (coleader Sheila Jordan)

LP 1982. Last Year’s Waltz, ECM 1213

CD1984. Mostly Ballads, New World Records 80351-2

CD 1986. The Vanguard Date, OWL 3819062

CD 1987. Life’s Magic, Blackhawk Records 522-2

CD 1988. Porgy, Evidence 22200

CD 1989. Jazz City Christmas, Jazz City 00036

CD 1989. Jazz City Christmas Vol. 2, Jazz City 00166

CD 1989. Oceans in the Sky, OWL R2-79232

CD 1991. Looking Back, Concord Jazz 4446

CD 1990. Live at Maybeck Recital Hall Vol 13, Concord Jazz 4484

CD 1991-92. Romeo and Juliet : Cinematic Jazz no 5, Cinema City 6497

CD 1991-92. 13 jours en France : Cinematic Jazz no 6, Cinema City 6498

CD 1991-92. Love story : Cinematic no 8, Cinema City 6500

CD 1992. Years Later, Conxord Jazz 4554

CD 1993. Aladdin - Cinematic Jazz N°13, Cinema City 8077

CD 1993. New Cinema Paradise – Cinematic Jazz N°14, Cinema City 8078

CD 1995. Remembering Tomorrow, ECM 2-1573

CD 1995. Seasons of Romance, Postcards 71009

CD 1997. Dedication, Reservoir 154

CD 1998. Countdown, Reservoir 157

CD 1999. Trio, TK 35081

CD 1999. The Best Things, Reservoir 162

CD 2000. Jazz and Emotions, (no information)

CD 2000. Sing Me Softly the Blues, Venus 35108

CD 2001. Quiéreme Mucho, Venus 35142

CD 2002. Pastorale, Sunnyside 1175

CD 2003. Love Walked In, Venus 35062

CD 2003. Temptation, Venus 35098

CD 2004. Promises Kept, ECM 1038 CD 2004. Promises Kept, ECM 1038

CD 2005. Quiéreme Mambo, Sunnyside 145

CD 2006. Pavane for a Dead Princess, Venus 35545

CD 2006. Together Again, Grappa 4247 (coleader Karin Krog)

CD 2006-10. Hilary Kole, You Are There: Duets, Justin Time 85612

CD 2007. Live at Birdland, Blue Note 373992-2

CD 2007. Two by 2, Owl Records 9847558 (coleader Steve Swallow)

CD 2008. Plays Standards, Venus 35395

CD 2008. Baubles, Bangles and Beads, Venus 1003

CD 2009. Mostly Coltrane, ECM 2701114 2099

CD 2008. Life's Backward Glances, ECM 1779946 (coleader Steve Slague-Michael Smith)

CD 2010. I Will Wait for You : The Music of Michel Legrand, Venus 78190

CD 2012. Wisteria, ECM 2794578 2257

Sideman

CD 1957. Kenny Dorham, Jazz Contrasts, Riverside/Original Jazz Classics (OJC) 028

CD 1959. Ornette Coleman, Lenox School of Jazz/Concert, Royal Jazz 513

LP 1960. Kenny Dorham, Jazz Contemporary, Time 52004

LP 1960. Johnny Rae, Opus de Jazz Vol 2, Savoy 12156

CD 1961. Bob Brookmeyer / Stan Getz, Recorded Fall 1961, Verve 549 369-2

CD 1961. Stan Getz, Stan Getz Special Vol 1, Moon 040

CD 1961. Stan Getz, Tune Up, Natasha 4008

CD 1961-66. Stan Getz, Baubles, Bangles and Beads, Get Back Records 2032

CD 1963. Bill Barron, West Side Story Bossa Nova, Dauntless Records 6004

CD 1963. Stan Getz, with Guest Artist Laurindo Almeida, Verve 823 611-2

CD 1965. Art Farmer Quartet, Sing Me Softly of the Blues, Warner Jazz 7567807732 (LP Atlantic SD 1442)

CD 1965. Pete La Roca, Basra, Blue Note 8 32091-2 (LP 4205)

LP 1965. Don Heckman, Improvisational Jazz Workshop, Ictus 101

CD 1965. Stan Getz, The Vancouver Concert 1965, Gambit 69291

CD 1966. Oliver Nelson, Sound Pieces, Impulse!/GRD 103

LP 1966. Pee Wee Russell, College Concert of Pee Wee Russell and Henry Allen, Impulse! AS9137

CD 1966. Karin Krog, Raindrops, Raindrops, Crippled Dick Hot Wax 81

CD 1968. Lee Konitz, Alto Summit, Verve 843 139-2 (LP MPS Records 15 192)

CD 1975. Sheila Jordan, Confirmation, East Wind 8024

CD 1979. Steve Swallow, Home, ECM 513 424-2 1160

CD 1979. Bob Moses, Devotion, Soul Note 121173-2

LP 1980. Bob Moses, Family, Sutra 1003

CD 1981. David Darling, Cycles, ECM 843172-2 1210

CD 1983. Bob Moses, Visit with the Great Spirit, Gramavision 79507

LP 1983. Carol Fredette, Love Dance, Devil Moon 001

CD 1991. Steve Swallow, Swallow, WATT 314 511960-2

CD 1993. Carol Fredette, In the Shadows, OWL 830484-2

CD 1995. Carol Fredette, Everything I Need, Brownstone Recordings 9903 CD 1995. Carol Fredette, Everything I Need, Brownstone Recordings 9903

CD 1998. Stéphan Oliva, Jazz'n(e)motion, BMG/RCA Victor

CD 1998. Sheila Jordan, Jazz Child, HighNote 7029

CD 1998. Bob Moses, Nishoma, Grapeshot Records 9001

CD 2002. Bob Mintzer, Bop Boy, Pony Canyon Records 30047

CD 2002. Sheila Jordan, Little Song, HighNote 7096

CD 2003. Charles McPherson, But Beautiful, Venus TKCV-35182

CD 2006. Mark Masters , Wish Me Well, Capri 74078

CD 2008. George Garzone, Among Friends, Stunt 09022

CD 2011. Jazzanova, Coming Home by Jazzanova, Stereo Deluxe 20927

CD 2011. Tessa Souter, Beyond the Blue, Motéma Music 87

Videos

2013 Interview lors du Montreal Jazz festival

2012 Steve Kuhn Trio - Confimation

2012 Steve Kuhn Trio - Trance et + Oceans in the sky

2012 Steve Kuhn Trio Trance into Oceans in the Sky William Paterson U

2012 Steve Kuhn Trio - Jazz à Foix 2012

2012 Steve Kuhn Trio - Minuet #4 de Bach – TVJazz.tv

2011 Live at Duc des Lombards Dean johnson (b) Joey Barron (dm) Mostly Coltrane

2011 Jazz Is Intoxicating with Derrick Gardner (tp), Avery Sharpe (b), Steve Johns (dm)

2010 Interview Montreal Jul 4, 2010

2008 Joe Lovano / Steve Kuhn Quartet "Remembering John Coltrane" Fragment 1

2008 Joe Lovano / Steve Kuhn Quartet "Remembering John Coltrane" Fragment 2

2008 Joe Lovano / Steve Kuhn Quartet "Remembering John Coltrane" – jazz Baltica David Finck (b), Joey Barron (dm) Impressions

2008 Joe Lovano / Steve Kuhn Quartet "Remembering John Coltrane" – jazz Baltica David Finck (b), Joey Barron (dm) My Little Brown Book

2008 Joe Lovano / Steve Kuhn Quartet "Remembering John Coltrane" – jazz Baltica David Finck (b), Joey Barron (dm)

2007 Steve Kuhn Sings + Sheila Jordan New yrok 2007

2004 Sheila Jordan & Steve Kuhn Trio - Blackbird - Chivas Jazz Festival Brasil

Trio in Napoli David Fink Bass + Billy Drummond

*

|

|